Readers, Writers, Texts 1: Advertising and Representation

Advertising is one of the most pervasive forms of communication in human history, shaping societies and influencing consumer behaviour for thousands of years. From the earliest inscriptions promoting goods in ancient marketplaces to the polished campaigns of the twentieth century’s ‘golden age,’ advertising has evolved alongside technology, culture, and economics. Today, it is not only a tool for selling products but also a powerful force that constructs identities, values, and social norms. Modern advertising is multimodal, combining text, image, sound, and movement to create persuasive visual narratives. In this section you’ll find out how to decode the visual narrative of advertising images, see how ads reinforce or challenge gender stereotypes, and learn how racial and ethnic stereotypes are constructed to sell products and perpetuate beliefs about different kinds of people.

Topics:

IB Learner Profile: Principled

We act with integrity and honesty, with a strong sense of fairness and justice, and with respect for the dignity and rights of people everywhere. We take responsibility for our actions and their consequences.

How principled are you when it comes to the products you consume? Advertising and the mass media are powerfully persuasive and, in today’s digital world, positive messages are amplified and strengthened to the point where they are difficult to resist. As you study this section of the course, consider your own principles in light of the brands you purchase, the products you consume – and the messages you believe.

Readers, Writers, Texts 2: The Language of Persuasion

Have you ever experienced goosebumps while listening to someone speak? That reaction is often the power of persuasive language at work. Persuasion is behind countless texts from school presentations and political speeches to advertising campaigns convincing you to buy something you never planned to. In this section, you’ll explore the mechanics of persuasion and its impact on audiences. Begin by examining classic tools such as propaganda, rhetoric, and public speaking, before moving into the modern world of persuasion where techniques like greenwashing blur the line between truth and marketing. You’ll learn how to question both the methods and the messages behind persuasive texts, and how to identify logical fallacies that weaken arguments. Finally, confront the darker side of persuasion when words turn toxic, discovering how language can be weaponised in debates about migration and identity.

Topics

IB Learner Profile: Communicator

We express ourselves confidently and creatively in more than one language and in many ways. We collaborate effectively, listening carefully to the perspectives of other individuals and groups.

Do you express ideas clearly and interpret messages thoughtfully? Being a communicator in the context of persuasive language means more than speaking or writing well; it requires understanding how meaning is constructed and shared. In this section, you will learn how words, images, and tone are used to influence audiences, and how these techniques shape public opinion. Communicators engage critically with the messages they encounter, asking not only what is being said, but how and why.

Readers, Writers, Texts 3: News, Information, and Public Opinion

Public opinion is shaped by the stories we read, the images we see, and the voices we hear – and at the heart of this process is the news. This section explores how the news is made and how it influences the way societies think and act. You’ll examine the concept of ‘newsworthiness’ – what makes a story ‘news’ – and how factors such as sensationalism affect the stories that reach the public. You’ll consider how photojournalism can influence interpretation, how a single image can be more powerful than words, and even (occasionally) change the course of history. Above all, you’ll address ethical challenges faced by journalists, especially the tension between a commitment to truth and the commercial interests of media organisations, and how this gives rise to the biases and subjectivity that is an unavoidable side-effect of curating real world events for a media audience.

Topics

IB Learner Profile: Knowledgeable

We develop and use conceptual understanding, exploring knowledge across a range of disciplines. We engage with issues and ideas that have local and global significance.

This section encourages you to think critically about the media you consume. How do you get your knowledge of the world? Which newspapers do you read, or news programmes do you watch, if any? How wide or narrow is the range of sources you use to keep abreast of current affairs? An IB Learner should strive to be knowledgable about ideas of global significance, and watching or reading the news from a variety of sources can help you broaden your horizons in this regard.

Time and Space 1: Language On the Move

One of the core concepts you will return to throughout your study of IB English is that language changes in relationship to time and space. This is what makes language so fascinating – and admittedly challenging – to study. In this section, you will explore varieties of English that may feel familiar and others that might surprise you, considering how language evolves across regions, cultures, and historical periods. Once solely the language of a cold, small island in the North Atlantic, English spread globally through trade, colonisation, and cultural exchange, becoming the world’s most widely used lingua franca. Today, English is spoken by billions… but it is far from uniform. As it travels, English transforms, absorbing local words, adapting to new contexts, and developing distinct regional and cultural varieties. These changes reflect the dynamic nature of language and the diverse identities of its speakers. You’ll see how modern attitudes toward non-standard English raise important questions about power and inclusion. Who decides what counts as ‘proper’ English? How do judgments about language affect opportunities and perceptions of others? In exploring these issues, you will consider not only the history and spread of English but also what linguistic diversity means for global communication today.

Topics:

IB Learner Profile: Inquirers

We nurture our curiosity, developing skills for inquiry and research. We know how to learn independently and with others. We learn with enthusiasm and sustain our love of learning throughout life.

Inquirers like to learn beyond the confines of the classroom and are curious to discover more about the world. But learning doesn’t always have to be a chore. RobWords (Rob Watts) is a British linguist who runs a popular YouTube channel dedicated to the history and quirks of language. His clear, engaging explanations of etymology and word origins makes linguistics accessible and fun. Rob explains how English has evolved through connections with other languages, making him a great resource for anyone curious about English and its roots. In the spirit of being an inquirer, why not browse the titles in his video collection, choose one that appeals, and report back your discoveries at the beginning of a lesson?

Time and Space 2: Taboo or Not Taboo

Language changes across time and space, but it also reflects the values, beliefs, and taboos of the societies that use it. This section explores how language both reveals and reinforces cultural attitudes, and how it contributes to issues of prejudice and inequality. Taboo language is not just about ‘bad words.’ It raises deeper issues about what societies choose to silence or soften through euphemism and political correctness, and how these choices affect transparency and truth. You will investigate how taboos surrounding gender have historically marginalised women, and how modern mental health taboos have harmed men by discouraging openness and vulnerability. By studying these issues, you’ll develop an awareness of how language reflects – and can be used to challenge – social hierarchies. Understanding how language perpetuates inequalities will help you better navigate a world where words carry so much weight.

Topics:

IB Learner Profile: Caring

We show empathy, compassion and respect. We have a commitment to service, and we act to make a positive difference in the lives of others and in the world around us.

IB Learners care about others, and care about the impact they have on others. They don’t stand aside when they see injustice or cruelty, and seek ways to actively improve the lives of others. The notion of ‘action’ is tied intimately to caring; so at some point while you investigate the following topics pause and draw up a resolution. This could be as small as altering the words you use to describe others, or something larger like delivering a presentation in an assembly about the way the language we use can be culturally sensitive.

Time and Space 3: Explorations: Travels Through Space and Time

This section takes you on a journey through different ideas and perspectives, loosely connected by the theme of travel and exploration. Rather than following a single path, you can dip into a range of topics such as exploring the genre of travel writing and photography, considering how the search for beauty in an Instagram feed can influence the way cultures are represented; or look at the history of Orientalism and the exoticisation of ‘other’ people. Alternatively you can sidestep to exploring depictions of poverty and ask how words and images are able to reduce individuals to stereotypes. Whichever route you choose to take, you’ll consider alternative approaches that challenge common assumptions and restore dignity to those portrayed in words and images. Through different explorations, hopefully you’ll develop an awareness of how language and visual storytelling can both connect and divide us.

Topics:

Learner Profile: Thinker

We use critical and creative thinking skills to analyse and take responsible action on complex problems. We exercise initiative in making reasoned, ethical decisions.

This section encourages you to be a thinker by engaging with complex and sometimes uncomfortable questions about representation, ethics, and cultural narratives. As you explore travel writing, photography, orientalism, and depictions of poverty, you will need to analyze how language and images construct meaning and influence perception. Being a thinker means approaching these issues critically by questioning assumptions and identifying biases.

Intertextuality 1: Making Connections

All texts carry meaning, but discovering that meaning is not always straightforward. When we read, we interpret, but interpretation today is understood as more than just finding a single ‘hidden message.’ Modern theory suggests that every text is connected to other texts, traditions, and cultural influences. Reading becomes more than looking at one text in isolation. It’s like traveling through a landscape of ideas, where every work leads you to others. This network of connections is called ‘intertextuality’. In this section, you’ll see how texts borrow ideas, styles, and structures from one another in various ways. You’ll learn to compare and contrast literary works, examine the difference between ‘high’ culture and ‘low’ culture, and consider why writers and creators make mash-ups, blending genres, references, and genre codes to create something new.

Topics:

IB Learner Profile: open-minded

We critically appreciate our own cultures and personal histories, as well as the values and traditions of others. We seek and evaluate a range of points of view, and we are willing to grow from the experience.

This part of the course could have been tailor-made by somebody with the value of open-minded in mind. In order to fully understand and appreciate the concept of Intertextuality, you will have to be open to all kinds of texts, and even open to the idea that, in order to understand and appreciate one text, you have to have read many other – possibly unrelated – texts first!

Drama Study: Death and the Maiden by Ariel Dorfman

Fans of psychological thrillers, courtroom dramas, and intense themes of revenge and justice will be drawn to Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden. Written after the writer’s exile from Chile, the play is set in an unnamed post-dictatorship country, representing Dorfman’s lost home. Having adopted a democratic government, the country faces many challenges in its attempt to return to stability after upheaval.

The plot focuses on married couple Gerardo Escobar and Paulina Salas. As the play opens, Gerardo’s car breaks down at night and he accepts the offer of a passing stranger, a doctor named Roberto Miranda, to help him. Inviting him home and letting him stay the night rather than drive further in the dark, this seemingly trivial incident kickstarts an intense drama involving kidnapping, traumatic flashbacks, and violent confrontation. Paulina, upon hearing the doctor’s voice, suspects that he is in fact a member of the secret police who kidnapped, raped, and tortured her years ago. Taking matters into her own hands, to the horror of her husband, Paulina kidnaps Roberto, ties him up, and confronts him in the house.

Drama Study: The Visit by Friedrich Durrenmatt

The impoverished town of Guellen looks to multi-milliionaire Claire Zachanassian for financial salvation. When she offers them a million dollars if they kill Ill, a citizen of the town and her former lover, the townspeople initially refuse – but their resolve is worn down by the allure of wealth. Will they hold on to their moral idealism, or will the lure of money prove too much to resist?

The Visit, written in 1956, was Dürrenmatt’s third published work and is set approximately ten years after the end of the second world war. Famously, Switzerland remained neutral throughout the conflict, siding with neither Allied nor Axis forces. However, Switzerland had deported its Jewish citizens, refused to allow migrant Jews fleeing the Nazis to enter Switzerland, hosted Allied soldiers in prisoner of war camps, and accepted looted gold from German forces. In Dürrenmatt’s opinion, ‘neutrality’ was merely a euphemism for ‘complicity’. Therefore, his play is set in Guellen, a thinly veiled representation of Switzerland; a community forced to choose between moral convictions and material gain.

Drama Study: Top Girls by Caryl Churchill

Since premiering in 1982 at the Royal Court Theatre London, and its successful Atlantic crossing to New York later that year, Top Girls has been regarded as a seminal play about the difficulties faced by women in the world of work and society at large. Mixing fantasy and reality, using a nonlinear construction, and featuring overlapping dialogue as women speak across, on top of, and around one another, Top Girls is both unique and difficult. Beginning with a surreal, imaginary dinner party scene that celebrates the promotion of Marlene to managing director of Top Girls Employment Agency, Churchill asks questions about what it takes for a woman to be successful, and to what extent 20th century Feminism has equaled out historical injustices for women.

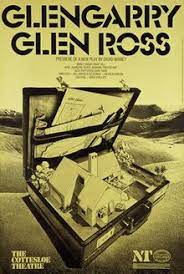

Drama Study: Glengarry Glen Ross by David Mamet

Glengarry Glen Ross, by American playwright David Mamet, was first performed by the Royal National Theatre, in London, England, on September 21st 1983. Critic reviews were overwhelmingly positive and the production played in front of sold-out audiences. The play opens in a Chinese restaurant in Chicago. Three pairs of men sit in different booths, eating and talking. They all work for the same real estate sales office across the road. Bit by bit, we discover that there is a sales contest on: the winner of the first prize will receive a Cadillac; second prize a set of steak knives – all the rest of the salesmen will be fired! The second act relocates to the sales office the next morning: it has been ransacked and a set of important “leads” – information about potential buyers – has been stolen. A police detective is there to investigate the burglary and one by one the salesmen are interrogated. It seems that one of them is the prime suspect.

Drama Study: The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare

Merchant of Venice ranks with Hamlet as one of Shakespeare’s most frequently performed dramas. Written sometime between 1594 and 1598, the play is primarily based on a story in Il Pecorone, a collection of tales and anecdotes by the fourteenth-century Italian writer Giovanni Fiorentino.

In Venice, Antonio and Bassanio are friends. Bassanio is already in debt to the merchant, but he asks for an additional sum so that he can woo the wealthy and beautiful Portia in Belmont. Because most of his money is invested in three merchant vessels that have not returned from abroad, Antonio is unable to comply with his friend’s request. Bassanio turns to Shylock, who hates Antonio because he is a Christian and because he lends money without interest. Shylock agrees to lend Antonio 3,000 ducats for three months: if the loan is not repaid in time, he will demand a pound of the merchant’s flesh.

Drama Study: Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw

When George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1925, he was praised for turning “his weapons against everything that he conceives of as prejudice.” This is clearly true of Pygmalion, which was premiered in German in Vienna in 1913.

The play is a modern interpretation of an ancient myth, the tale of Pygmalion and Galatea. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Pygmalion, an artist, falls in love with Galatea, a statue of an ideal woman that he created. Pygmalion is a man disgusted with real-life women, so chooses celibacy and the pursuit of an ideal woman whom he carves out of ivory. Wishing the statue were real, he makes a sacrifice to Venus, the goddess of love, who brings the statue to life. By the late Renaissance, poets and dramatists began to contemplate the thoughts and feelings of this woman, who woke full-grown in the arms of a lover. Shaw’s central character—the flower girl Liza Doolittle—expresses articulately how her transformation has made her feel, and he adds the additional twist that Liza turns on her “creator” in the end.

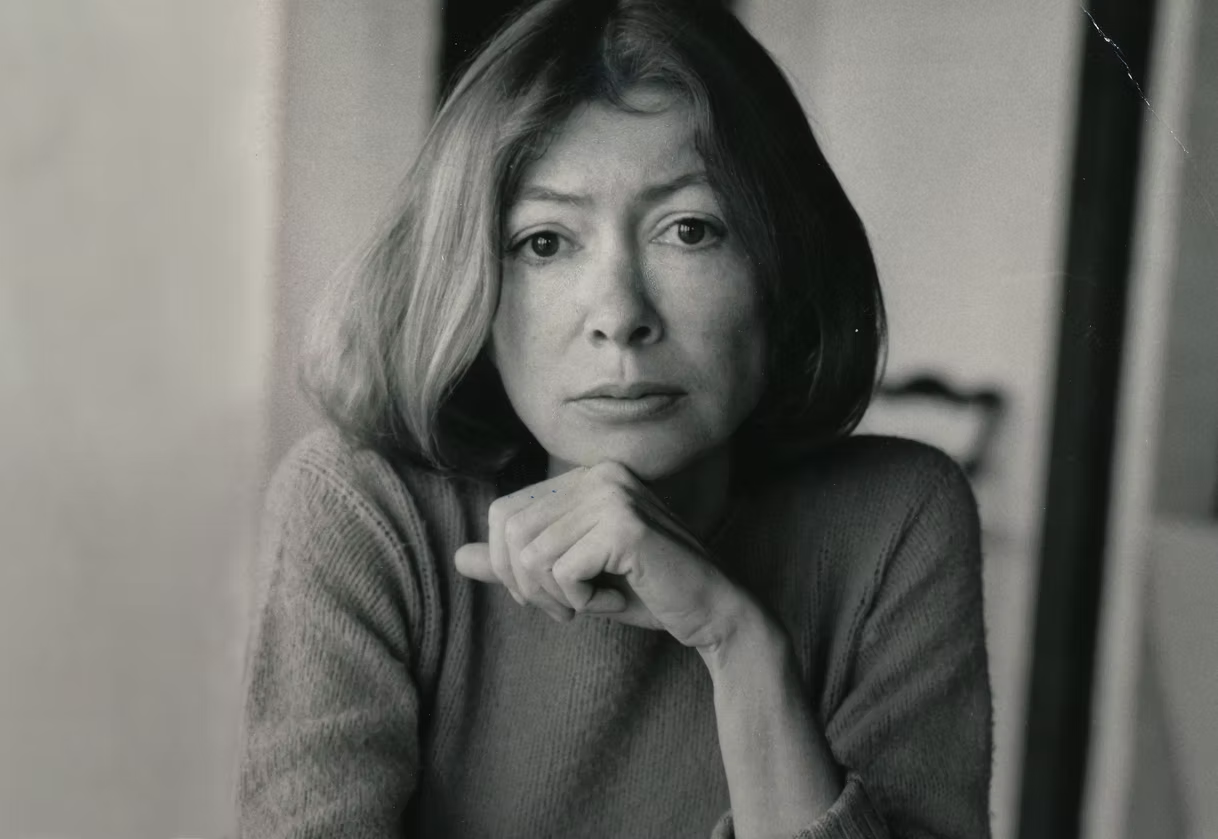

Prose Study: Play It As It Lays by Joan Didion

Maria (rhymes with ‘pariah’) Wyeth is a 31-year-old model and actress who lives in the famous uptown Hollywood suburb of Beverly Hills. The novel opens a month after her friend BZ’s suicide and Maria has been in a psychiatric hospital ever since. We read Maria’s account of events that the doctors have asked for so they can help her recover from an emotional breakdown. She tells us of her childhood in Nevada, and her leaving home at the age of 18 to become an actress.

Play It As It Lays is Joan Didion’s second novel and one of her most famous. Named in TIME’s 100 Best Books (1923 – 2005) it was adapted into a film by Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne. The book itself is brisk, 200 pages long but divided into 80 short chapters, some of which are only a few sentences each. Her energetic style, and focus on using dialogue to tell the story, creates an episodic, fast-paced narrative that is the perfect framing for the quintessential ‘Hollywood novel’.

Prose Study: No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai

No Longer Human is the most famous of author Osamu Dazai’s (pen name of Shuji Tsushima, or 太宰治 in Japanese) few works. Written in 1948, it was first published in Japan under the name Disqualified From Being Human. Dazai’s book deals with themes of mental illness, depression, alienation, abuse, addiction, and suicide, seeming to uncover all of humanity’s darkest inclinations and tragedies. As a confessional work (in Japan, this type of autobiographical fiction is called an I-novel), the story echoes Dazai’s own unfortunate downward spiral. Yozo’s alcohol and morphine addictions, his failed relationships and attempted suicides all cleave close to Dazai’s real-life experiences.

Prose Study: A Thousand Years of Good Prayers by Yiyun Li

From the hustle and bustle of Beijing, to the bleak and barren steppes of Inner Mongolia, to a tiny restaurant in Chicago, Yiyun Li’s stories take readers to places strange and familiar, comfortable and bewildering. The debut collection of writer Yiyun Li (李翊雲 in Chinese), A Thousand Years of Good Prayer was published in 2005 and explores the lives, marriages, past loves, beliefs, and struggles of people caught between eastern and western cultures. Born in China during the Cultural Revolution, studying in Beijing, and moving to the United States to complete her degree in immunology, Yiyun Li is ideally placed to explore the effects of migration and political upheaval on individuals, parent-child relationships, and even on one’s own memories. Until recently a professor of creative writing at Princeton University, Li is the author of five novels, a memoir and two collections of short stories.

Prose Study: Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress by Dai Sijie

The narrator, then 17, and his best friend Luo, who is 18, are sent to the Phoenix of the Sky mountain where the two urban youths are to be re-educated by poor village-dwelling peasants. They arrive streaked with mud from their journey, and immediately the villagers seize all their possessions, including a violin that they believe to be a toy. Then Luo smoothly breaks in with an offer to play a sonata called, ‘Mozart Is Thinking of Chairman Mao.’ The village headman smiles. So begins the story of Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress.

Dai Sijie’s own experience of being sent to live among peasants during the Cultural Revolution was the inspiration for Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, which is semi-autobiographical. After returning home, he taught at a school in Chengdu before receiving a scholarship to study film in France. He left China in 1984. He directed several films before turning to writing. Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress was his first novel, winning several French literary awards, been adapted into a film by Dai himself, and been translated into 25 languages.

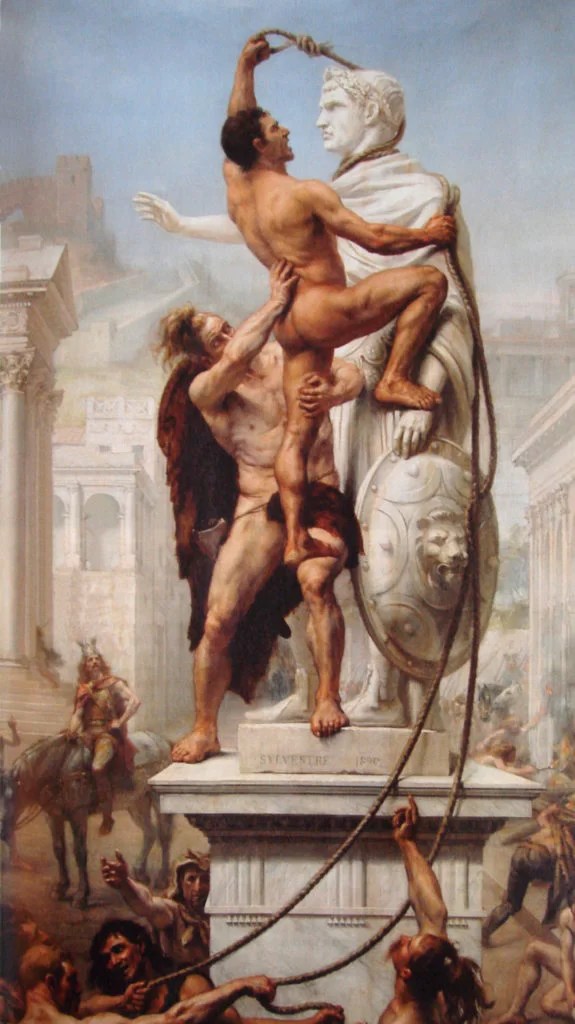

Prose Study: Waiting for the Barbarians by J.M. Coetzee

An unnamed magistrate is stationed at a frontier border town of an expanding empire. He’s been posted here for a long time and, despite how far away he is from the capital, he is happy to live out his ‘easy years’ in this remote area on the border of the empire; approaching sixty, he will retire soon and, apart from the occasional sheep raids and sporadic attacks, his posting is not at all dramatic. However, rumour is spreading about a possible barbarian attack by the indigenous peoples who live on the empire’s fringes. Displaced by the foreign settlers, are they now massing together to counter-attack?

The magistrate’s easy days are thrown into turmoil by the arrival of Colonel Joll. A ruthless army man, he’s been sent from the capital to discover the truth about the barbarian invasion. The magistrate welcomes Joll uneasily, and soon his suspicions about the officer’s mission are borne out. Joll ruthlessly adopts brutal torture tactics to discover the ‘truth’ from nomadic prisoners abducted from the desert lands around the settlement. The magistrate is repulsed by these techniques, and by the death of an elderly father who could not bear the sight of his daughter being tortured in front of him. Because of his compassion, he is reluctantly drawn into conflict with the empire he is meant to serve.

Prose Study: The Vegetarian by Han Kang

Han Kang’s The Vegetarian is one of the most internationally well-known Korean novels. It is not a story about a vegetarian per se; rather, it is a work that investigates what constitutes suffering. It tells the story of Yeong-hye as related through the eyes of three members of her family: her husband, her brother-in-law, and her sister In-hye. The story begins when Yeong-hye, seemingly from out of the blue, tells her husband she will no longer eat meat and proceeds to throw all the meat in their house away. However, in Korean society, social conformity is regarded as one of the most important social virtues. Yeong-hye’s refusal to eat meat therefore brings considerable embarrassment to her husband and father. So her decision backfires into a devastating conflict against an almost indomitable enemy: the reigning norms of the patriarchal Korean society of which she is also a member. When she determines to quit eating meat, all of society, including her own husband and family members, turn their backs against her and become her enemy.

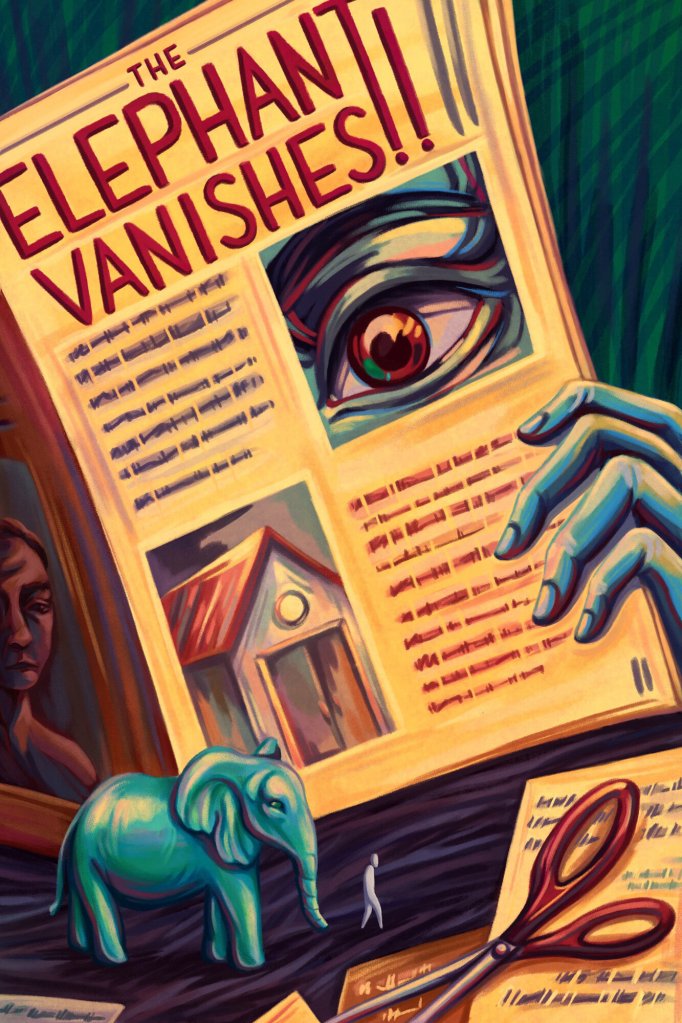

Prose Study: The Elephant Vanishes by Haruki Murakami

Haruki Murakami (in Japanese, 村上 春樹) was born in Kyoto in 1949 and moved to Tokyo to attend Waseda University. After college, Murakami opened a small jazz bar, which he and his wife ran for seven years. If you are ever in Tokyo you can still visit the Peter Cat today. Murakami’s love of music pervades his books. Many of his characters pass the time listening to music and even the title of a well-known novel is named after a Beatles song: Norwegian Wood.

His first novel, Hear the Wind Sing, won the Gunzou Literature Prize for budding writers in 1979. He followed this success with two sequels, Pinball, 1973 and A Wild Sheep Chase, which all together form “The Trilogy of the Rat.” Since then Murakami has written over a dozen novels, works of non-fiction and short story collections, including The Elephant Vanishes (originally published in 1993). His work has been translated into more than fifty languages, and nominated more than once for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Prose Study: Broken April by Ismail Kadare

The Charter of Paris for a New Europe (also known as the Paris Charter) was signed in 1990 by 34 participating nations – including every European country except Albania. This powerful novel reveals that Albania remained a closed country, haunted by the ghosts of the past and locked in a semi-medieval culture of blood and death. Broken April is one of several novels by Ismail Kadare that has been translated from Albanian into English and it’s simple style and power has lost nothing when read in translation.

The novel describes the way life is lived in the high mountain plateaus of the country, where people follow an ancient code of customary law called the Kanun that has been handed down from generation to generation. The code demands men to take the law into their own hands. Insults must be avenged, family honour must be upheld – and blood must be spilt.

Prose Study: The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter

Published in 1979, The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories retells classic fairy tales in a disturbing, blood-tinged, explicit way. Angela Carter revises Sleeping Beauty, for example, from an adult, twentieth-century perspective. You might think that fairy tales are the sorts of stories to read to children in bed to lull them to sleep – not these versions! Her renditions are intended not to comfort but to disturb and titillate.

In the title story of the collection, The Bloody Chamber, a young woman is traveling by train from Paris to her new home, a fairy tale castle seemingly out of legend. Her husband is asleep near her, and she, a young pianist, lies sleepless, not knowing what to expect of her married life. Her husband, a marquis who is much older than she and much richer than she, had three wives before her— an opera diva, an artist’s model, and a countess— all of whom died under mysterious circumstances. On arrival at the castle, her husband tells her she can go anywhere – except into a strange room that he always keeps locked.

Prose Non-Fiction: Nothing to Envy by Barbara Demick

The DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, commonly called North Korea) is notoriously hostile toward journalists. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, outsiders, when they were allowed to visit at all, were shepherded to the showcase capital of Pyongyang, sheltered from the poverty and famine found in most of the rest of the country. Barbara Demick is an American reporter who worked for the Los Angeles Times and was bureau chief in South Korea. She interviewed over 100 North Korean survivors and defectors, choosing six stories from people who lived in the industrial city of Chongjin to represent the experiences of the ordinary people of the country.

The timeline of Nothing to Envy charts the lead-up to the devastating North Korean famine (euphemistically called The Arduous March in the DPRK), a period of mass starvation that lasted from 1994 – 1999 in which between 2 and 3.5 million North Koreans lost their lives. As money and jobs dried up in the years before the famine, people started to fear the worst. Even the government regime, so reluctant to accept anything might be wrong in their workers’ paradise, instigated a propaganda campaign exhorting people to eat less food. Not that the people had much choice. By the mid-1990s, the countryside was stripped bare and mothers resorted to making soups out of grass, and porridge out of tree bark, rice husk and sawdust.

Prose Non-Fiction: Fun Home by Alison Bechdel

Subtitled ‘A Family Tragicomic’, Fun Home is a graphic novel recounting the story of Alison Bechdel coming out as a lesbian. Told in non-chronological flashbacks to her childhood in Beech Creek, a small rural town tucked into the Allegheny Mountains, Pennsylvania, the story is also a way of Bechdel making sense of her father’s death by comparing his life to her own. Throughout the novel, Bechdel works through her difficult childhood relationship with her father, Bruce, and her gradual discovery that he, too, harboured secrets from Bechdel, her mother and siblings. Bechdel remembers her father’s impatience, how quick he was to lash out in punishment, and how insecure he felt about his appearance. Although to the rest of the community, the Bechdel household represented the ideal ‘nuclear family’, her father’s secrets would come to undermine everything Bechdel thought she believed and risked making her childhood memories nothing more than a sham.

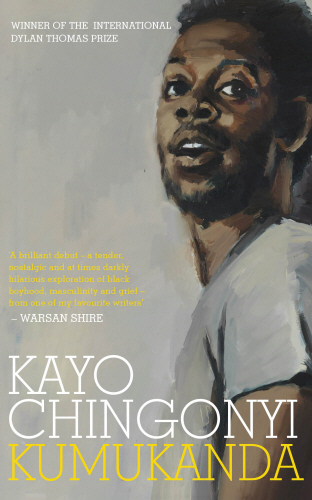

Poetry Study: Kumukanda by Kayo Chingonyi

Kayo Chingonyi’s first published poetry collection is called Kumukanda, a word from Luvale, his father’s first language from the country of Zambia where Kayo was born. Meaning ‘initiation’, it’s the name given to the rituals that mark the passage into adulthood of Luvale, Chokwe, Luchazi and Mbunda boys, from Zambia. As part of these rites, the boys live away from their homes in the bush, where they are taught traditional skills, learn the history of their tribes, and receive wisdom that takes them into manhood. A special day, makishi, marks the return of the initiated as men, and a celebratory festival is held. In an author’s note, the writer explains that this poetry collection “approximates such rites of passage in the absence of my original culture.”

It’s this process that forms the heart of kumukanda, the name of both this poetry collection and its central poem, the one that Kayo says he found most difficult to write. Following the death of his father when he was six years old, Kayo’s mother – who was studying in the UK – came to fetch him to live with her. As a result of disagreements following his father’s passing, Kayo became disconnected from his Luvale family, not speaking to anybody from his father’s side since 1993. Instead, he embraced aspects of British culture, especially Black British music culture such as grime and rap music, to negotiate his own rite of passage from boy to man.

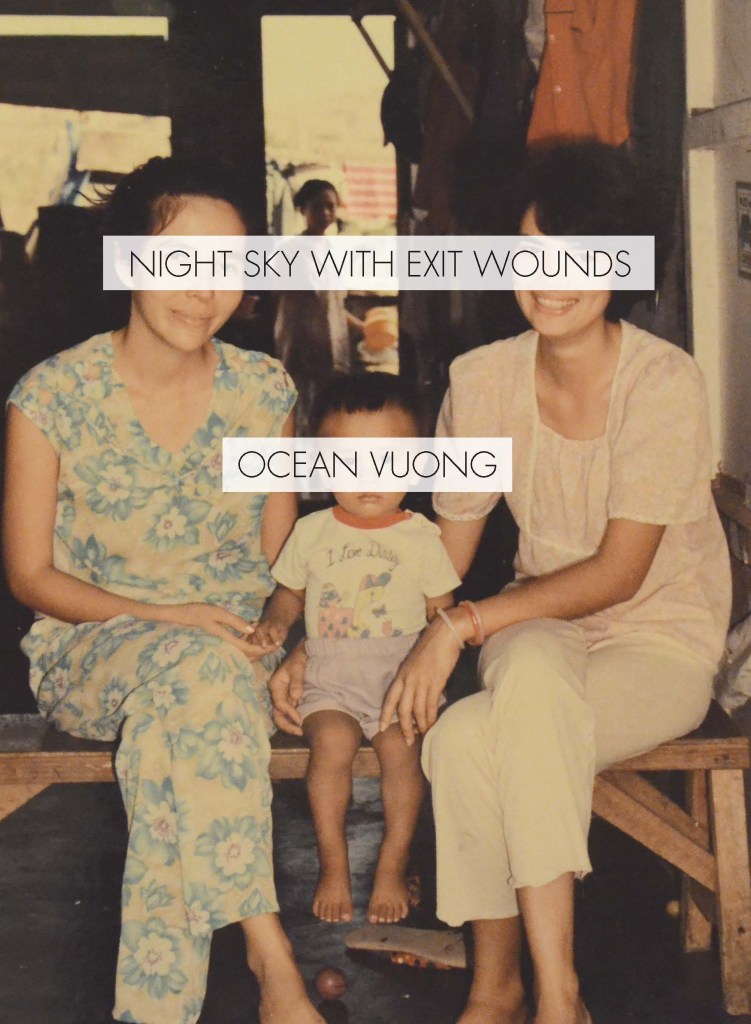

Poetry Study: Night Sky With Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong

Ocean Vuong was born in 1988 in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Though the Vietnam War had already ended more than a decade ago, its trauma had lasting consequences. During the war, Vuong’s white American grandfather married his maternal grandmother from the Vietnamese countryside. When the war ended, Vuong’s grandfather, who had gone back to visit home in the US, was not allowed to return to Vietnam. The family was further fractured when Vuong’s grandmother separated his mother and her siblings in orphanages in an attempt to secure their survival. Later, the family was forced to flee Vietnam when the police became suspicious of Vuong’s mother’s mixed heritage.

Night Sky With Exit Wounds explores the experience of growing up in a family fractured by conflict. Soon after arriving in America, Vuong’s father, suffering from PTSD and alcoholism, left the family, leaving him in the care of his mother, aunt and grandmother. To a large extent, this book is Vuong’s attempt to rediscover who his father really was, and who Ocean is today as a result of his upbringing.

Poetry Study: The Farmer’s Bride by Charlotte Mew

On a modest London street in Bloomsbury in 1913 called Devonshire Street stood a tiny independent bookshop by the name of The Poetry Bookshop. It’s proprietor was Harold Munro, and he ran this friendly neighbourhood store until 1926. As well as selling books of poetry, Harold also published – and it’s thanks to him that Charlotte Mew, a sometimes shy-and-silent young woman from Bloomsbury, found her audience. Invited to the shop by Harold’s assistant Alida Klemantaski, while Mew had never sought fame, she was quickly caught up in the whirl of poetic activity – and agreed to the publication of The Farmer’s Bride in 1916.

Despite the moderate success of The Farmer’s Bride, during her lifetime (1869 – 1928) Mew amassed no large following. However, in the last few decades there has been a renewed interest in Mew’s prose and poetry and a re-evaluation of her contribution to literature. In 2021 a new biography of Charlotte Mew, This Rare Spirit by Julia Copus, was released and it seems that Charlotte Mew is belatedly having her moment in the spotlight. I hope that the poems you read on this course will introduce you to her distinctive voice and that you will enjoy reading poems by a person Virginia Woolf once called “the greatest living poet.”

Poetry Study: John Keats’ Ode Sequence

For many, John Keats fits the quintessential image of a tortured-artistic-genius. Born on 31st October 1795 as the eldest son of Thomas and Frances Keats, his origins were working class. His father was a stable-keeper and it is rumoured the poet might have been born in the stables of the public house in Smithfields, London, where his father worked (and which was owned by his maternal grandfather). His early years and family life were happy and comfortable: the poet grew up with brothers George and Thomas and sister Fanny, who was born in 1803. Despite their working-class background the family were comfortable enough to let John attend a small village school in Enfield. Far from the studious, bookish and sensitive child we might expect, John’s classmates reported that he was robust and healthy – and he particularly enjoyed fighting!

Poetry Study: The World’s Wife by Carol Ann Duffy

First published in 1999, this collection of poems by Carol Ann Duffy presents stories, myths, and fairy tales popular in western culture. But this time we hear them from the point of view of women; the unsung, silenced or marginalised women close to famous men. Traditionally these women may have had no names; some of the poems’ titles follow a pattern (‘Mrs Midas’, ‘Mrs Darwin’, ‘Pygmalion’s Wife’ and so on) which bitterly suggests that women have been so neglected by history and culture the only way they can be identified is by association with their husbands’ name.