How to approach IBDP Language and Literature and IBDP Literature Paper 2

Whether you are a standard or higher level student, Paper 2 tests your ability to compare and contrast the literary works you have studied on your course. In fact, the paper is the same for both higher level and standard level students. You will be give a choice of four ‘open’ questions and you will have 1 hour and 45 minutes to compare and contrast the content, form and writing features of two literary works of your choice in light of the question you choose to answer. There are 25 marks available in this paper, which represent 35% of your grade at SL and 25% at HL. The only rule you must follow when choosing your works is you may not write about a literary work that you have used for a previous assessment. That means that the work(s) you discussed in your Individual Oral Presentation and your HL Essay (if you chose a literary work at all) are off the table. Despite this limitation, you should still have at least two literary works that you can use for this exam, and quite possibly a choice from more. Oh – and did I mention Paper 2 is a closed book exam? While this may seem like an unfair restriction, you’ll soon see that Paper 2 is less about memorising quotations and more about selecting moments and methods from your literary works that support your line of argument.

Whichever Language A course you have elected to study, in this section you’ll learn how to prepare for Paper 2, explore some different questions, see how to plan on the day, and discover how to structure and write a brilliant compare and contrast essay. You’ll find sample essays that have been written using the texts from your course which you can read and discuss, and you’ll be encouraged to prepare in the best way possible: by writing your own practice responses to sample questions.

1. Choosing the Best Question For You

Paper 2 is all about comparison and critical thinking. In the exam, you’ll face four open-ended questions, each inviting you to explore connections and contrasts between two literary works you’ve studied. These questions may focus on themes, characters, writer’s methods, reader’s interpretations – or they will be a mixture of these categories. Choosing the right question can make all the difference when the exam timer starts ticking, because the question you select determines how confidently and effectively you can develop your argument.

In this lesson, you will learn how to use the wording of each question to uncover its focus, reflect on your own strengths and knowledge, and decide which question types give you the best opportunity to showcase your understanding. Hopefully, after studying the PPT below, you’ll feel prepared to make a strategic choice under pressure and write with clarity, depth, and confidence:

Activity: Question Survey

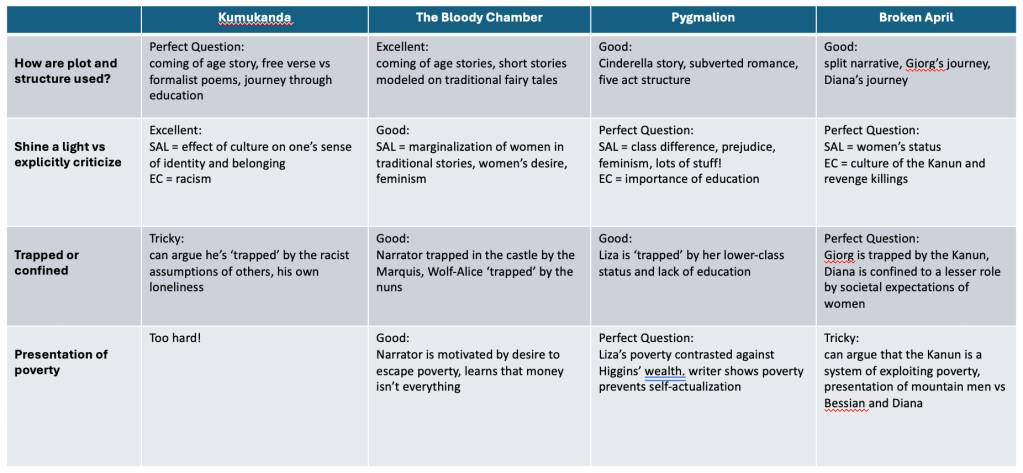

Not every Paper 2 question will suit every pair of works, which is how the paper is designed. You don’t have to answer all the questions – the key is knowing which questions give you the best chance to shine. In this activity, examine an exam paper provided by your teacher and rate each question against the literary works that are available for you to write about (remember, you can’t write about works you’ve already used in your IO or HL Essay). Is the question a perfect fit, a good option, a little tricky, or simply too hard to attempt?

Use the image above to create your own survey grid using the works you’ve studied and apply the same rating system to four questions you might encounter on Paper 2. This process will help you think critically about question focuses, whether it’s themes, characters, writer’s methods, reader interpretations, or a mix, and prepare you to make the best choice for you on the day of the exam.

2. Planning Tools

So you’re sitting in the exam room, you’ve chosen your question, and you’re itching to get started. But don’t rush ahead too quickly. Before you start to write, you should take some time to plan out your ideas and structure the way you’re going to write. When practicing for your Paper 2, there are two methods you should add to your toolkit: Venn Diagram and Graphic Organiser. Both have their advantages and disadvantages – it’s just a matter of deciding what works best for you.

When it comes to compare and contrast, a tried and tested planning method is the Venn diagram. Deriving it’s name from John Venn’s 1880s published maths papers, the humble Venn diagram has actually been used for centuries by philosophers and mathematicians to consider and organise logical relationships between two or more items – such as the two literary works you need to write about in your exam. A Venn diagram is a quick, visual way to map out similarities and differences between two works. It’s great for brainstorming and idea generation under time pressure and spotting overlaps at a glance. However, it can feel too simple for complex arguments and doesn’t show the depth or structure needed for a full essay.

If you want a method that is more thorough you can try using a graphic organiser to give you a clear, structured framework for planning. It helps you sort ideas into categories like themes, characters, and techniques, making it easier to build logical paragraphs. The downside? It takes longer to set up and can feel rigid, but it’s perfect for detailed, well-organized essays. During your preparation for Paper 2, try both methods and see which one works best for you. Display your diagrams and organisers in your classroom as helpful references for you and others to work with.

Activity: Brainstorm and Organise

For this task, choose one Paper 2-style compare-and-contrast question that you would like to work with and try to answer. Then select one of the two planning methods, Venn Diagram or Graphic Organiser, to map out your ideas. Use your chosen tool to identify key similarities and differences between your two works, organise ideas, examples, and techniques, and start shaping a clear argument. This activity is about turning a question into a structured plan that will make writing your essay easier and more effective. Once you’ve practiced with one method, why not try the other method with a different question and see which you prefer?

3. Revising Literary Works

“Trying to answer correctly a question or a problem that is difficult for us forces us to reflect, exercising multiple cognitive functions. Consequently, it generates better learning, even when the answer is incorrect. The more “mental sweat” it costs us to recover some of the memory, the better it will be anchored later…”

From Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning

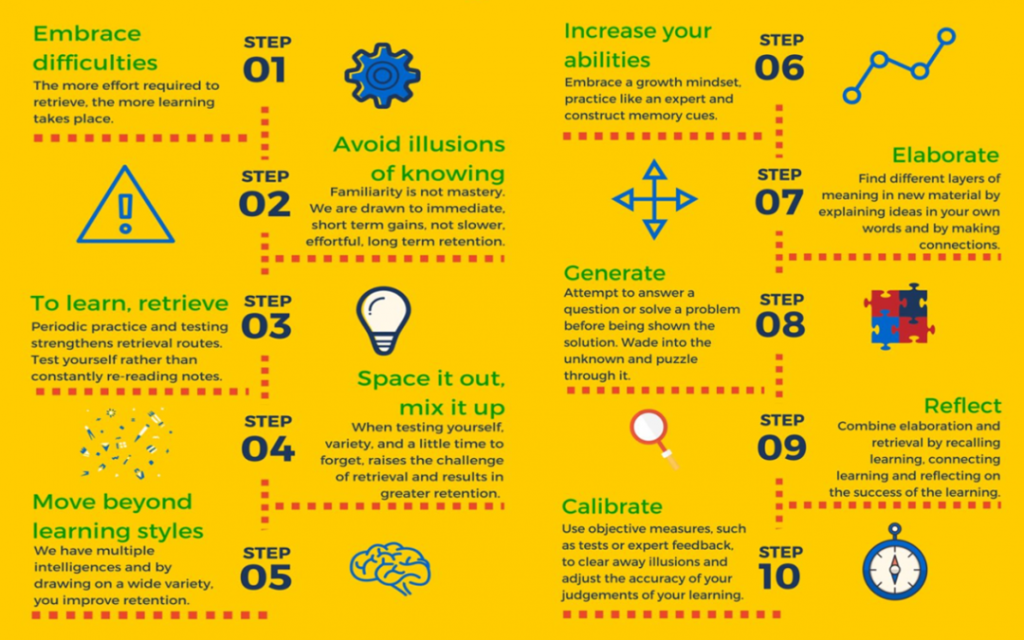

I’m not going to tell you not to reread the texts you want to write about in your paper 2 exam. And i’m not going to tell you not to review your notes either. What I am going to say is that these methods practiced by themselves create something called the ‘Illusion of Knowing.’ If ever you’ve tried to answer a question in class and said something like, “I know the answer but I can’t explain it right now,” you’ve experienced the illusion of knowing for yourself. You recognise material you’ve previously seen and your brain tricks you that you ‘get it’. Familiarity is not the same as mastery – in fact, familiarising yourself with your prior learning is only the second step in a ten step process identified in the book Make It Stick (see infographic below). To help you get a few steps ahead – all the way to step 7: ‘Elaborate’ – you’re going to have to get active.

Class Activity: Make Your Own Revision Guide

It’s not enough to simply reread what you’ve studied before. Writing in your own words generates more impact than passively reviewing what has been previously heard or read. It is useful, for example, to write a summary of what you remember immediately after reviewing your notes. Build structures by extracting the most important ideas and create a written framework for them. Don’t be afraid to explore new thoughts and ideas by connecting fresh concepts you’ve recently learned with previous concepts from your notes. After all, you may be working with texts you studied last week, last month, or even last year.

What’s more, the internet is chock full of tools that make this kind of work easier and more enjoyable. You might like to create a Padlet, collaborate with other people using Onenote, or use Canva to make a visually stunning booklet. You may know software that I’ve never even heard of, but would be perfect for making a revision guide to a literary work. Or you might prefer to work the old fashioned way with pen and paper, creating a poster, booklet or handout. However you choose to work, include in your revision guide: plot summary; setting; characters; themes; important symbols; key quotations (not too many, short and concise); the major literary features of the text; contextual information. Try to create as concise a revision guide as possible – and always try to use your own words rather than simply copying notes from one place to another. To empower yourself even further, explain your work to other students once you’ve finished.

Learner Portfolio: Practice for Paper 2

You know what they say: practise makes perfect. Undoubtedly the best way to prepare for any exam is to ‘Generate’ (refer to Step 8 in the Make It Stick infographic). There’s no getting away from it – paper 2 is a challenging exam. It’s probably one of your longest examinations and you might find it mentally and physically draining. It’s not easy to write for an hour and forty-five minutes, give or take. Generating sample answers of your own not only increases your familiarity with the texts you might use, but it will also help build your physical and mental stamina. You’ll make discoveries about the texts you read, find ways to explore complex issues, develop your own use of language and more, through the process of generation. Practicing earlier rather than later gives you time to ‘Reflect’ (step 9) and ‘Calibrate’ (step 10) as well.

Here is a selection of open questions in the style of the questions you’ll be given in the Paper 2 examination (there’s plenty more where these came from as well…) You can click on some of these questions to read sample answers that have been prepared as models for you to discuss and learn from. While all of these answers have clear strengths, none are perfect, so you might like to discuss how you would approach the questions differently or improve the answers. When you feel you are ready, choose any question and prepare an answer using your own choice of two literary works. Submit your answer for feedback, then add it to your Learner Portfolio:

- Some writers shine a light while others criticize explicitly. Compare and contrast these different approaches in two works of literature you’ve studied.

- Comparing the presentation of characters in two works you have studied, evaluate how the search for truth changes people.

- Discuss how conflict and resolution are treated in two literary works you have studied.

- Explain how two works you have studied present characters who are complex and multi-faceted.

- Implicitly or explicitly, literary works inevitably communicate cultural values to the reader. How have cultural values been conveyed in works of literature you have studied, and what effects have been achieved?

- Discuss the creation of setting and its role in creating a physical and/or emotional landscape in two works of literature you have studied.

- Discuss the ways in which two works you have studied demonstrate that the search for identity can be a conscious or unconscious process?

- Discuss how and why authors change the order of events in two literary works, and the effects created by these choices.

- Often the appeal for the reader of a literary work is the atmosphere a writer creates (for example, peaceful, menacing, or ironic). Discuss some of the ways atmospheres are conveyed, and to what effect, in two works of literature you have studied.

- If beauty is a relative term, how do two works you have studied explore this idea?

- How is ‘home’ depicted in two of the literary works you have studied, and what is its significance?

- In any two of the literary works you have studied, discuss the means as well as the effectiveness with which power or authority is exercised.

- Writers can present their ideas in unusual or thought-provoking ways. How, and to what effect, has this been shown in two works you have studied?

- Animals and images drawn from the world of animals are a rich source of inspiration for writers. Discuss how animals and natural images are used to develop central ideas in two works of literature you have studied.

- Works of literature can often function as social commentary. Discuss with reference to two literary works you have studied.

- Discuss how two works you have studied portray the concept of death.

- The struggle against injustice is a theme that speaks to readers. Compare and contrast the ways in which the authors of two literary works depict unjust worlds.

- Relationships are often central to literary works. How is this true of two works you have studied?

- ‘Fight or flight’ is a term used to describe human responses to adverse circumstances. Compare and contrast how the authors of two literary works you have studied depict responses to adverse circumstances.

- Consider the use to which music and/or musical elements have been made in two works of literature you have studied.

Further Reading

- Successful Learning According to Science – article at the Siltom Institute

Categories:Intertextuality