“‘Juxtapose a shocking image with a shocking headline and then you get a reaction”

MIchelle Katz, speaking to The Guardian about shock tactics in advertising

Mainstream media doesn’t just tell stories; it shapes what society considers acceptable and what remains hidden. Cultural taboos, those topics we rarely discuss openly, are often glossed over or disguised. In this section, you’ll see how some creators break through that silence using shock tactics and provocation. These strategies grab attention, challenge norms, and force us to confront uncomfortable truths. But provocation comes with risks: it can alienate, offend, or even reinforce stereotypes if used carelessly.

You’ll learn to recognise the signs of shock tactics and provocation when they are used in advertising, art, and social campaigns, asking why these methods work and what ethical questions they raise. But it’s not all doom and gloom – we’ll explore humour as a counterpoint to shock, a softer but potentially powerful tool. Satire, irony, and parody can expose hypocrisy and challenge taboos without triggering viewers’ defensive reactions. By comparing these approaches, you’ll learn how counter-cultural media navigates the fine line between visibility and censorship, and how creative strategies can illuminate the truth.

This section aims to develop critical awareness of the techniques that shape public discourse and the hidden forces behind what we see and what we don’t. Begin your investigation by choosing a couple of these articles to read, before trying out the lessons and activities below:

- Shock Advertising: From Awareness to Controversy (advertising blog)

- Why Shockvertising is So Good At Impacting Our Behaviour (blog at Creative Thinking)

- Charity Campaigns Cause Outrage… but Shock Sells (article at The Conversation)

- Shock Tactics (media article at The Guardian)

- Our Dangerous Addiction to Political Hyperbole (article at The Week)

- Why US Activists are Wearing Frog Costumes (at The Conversation)

- Domestic Violence Campaign Sparks Outrage (WPPI news article)

- A Look Back At Oliviero Toscani’s Most Provocative Campaigns (British Vogue magazine article)

- Have Charity Shock Ads Lost Their Power? (from The Guardian)

- Are Social Memes and Shock the Future of Charity Marketing? (from The Guardian)

Reading Challenge

This is a longer and more challenging piece of reading, but spending time on this piece, and discussing it with your teacher, will help you master this topic:

Discussion Points

After you’ve got your head around the material in this section, pair up, pick a question, spend five minutes thinking and noting down your thoughts – then discuss your ideas with a friend and report back to the class:

- When does shock cross the line into exploitation or harm?

- What happens over time as audiences become desensitised to shocking imagery? Does provocation lead to meaningful action or just outrage?

- Does showing violent imagery risk traumatising viewers? Or is it necessary to convey the gravity of certain issues?

1. Shock Factor

“We’re not selling tins of beans, we’re trying to save lives. Get noticed. Get talked about…”

Ian Heartfield, creative director at British advertising agency BBH

Shock and provocation have long been used as powerful tools in media to capture our attention and disrupt the complacency of audiences. At heart, these strategies work because they interrupt the ordinary flow of our thoughts and provoke strong emotional reactions. When we encounter something unexpected – whether it’s disturbing, controversial, or taboo – our cognitive patterns are jolted, making the message harder to ignore. This psychological effect is amplified by tapping into more primal emotions such as guilt, anger, fear, or empathy, which can drive people to act, donate money, or engage with a cause.

Charities and NGOs often employ shocking imagery to highlight suffering and injustice. Think of anti-smoking campaigns showing diseased lungs or animal rights groups exposing scenes of graphic cruelty. Artists, too, have embraced provocation to make social or political comments, using shock to challenge normative thinking and spark dialogue (Banksy’s street art is a prime example). Protest movements frequently stage dramatic stunts or visuals, such as Extinction Rebellion’s ‘die-ins’, to make their message impossible to ignore. Even middle-of-the-road campaigners leverage controversy through guerrilla marketing that disrupts conventional genres or narratives.

Use this PPT to discover more about how shock factor and provocation works on viewers, and to see some prominent examples of real world shock campaigns. While it probably goes without saying; caution is recommended when viewing images that are designed to shock:

Activity: Masterstroke or Misstep?

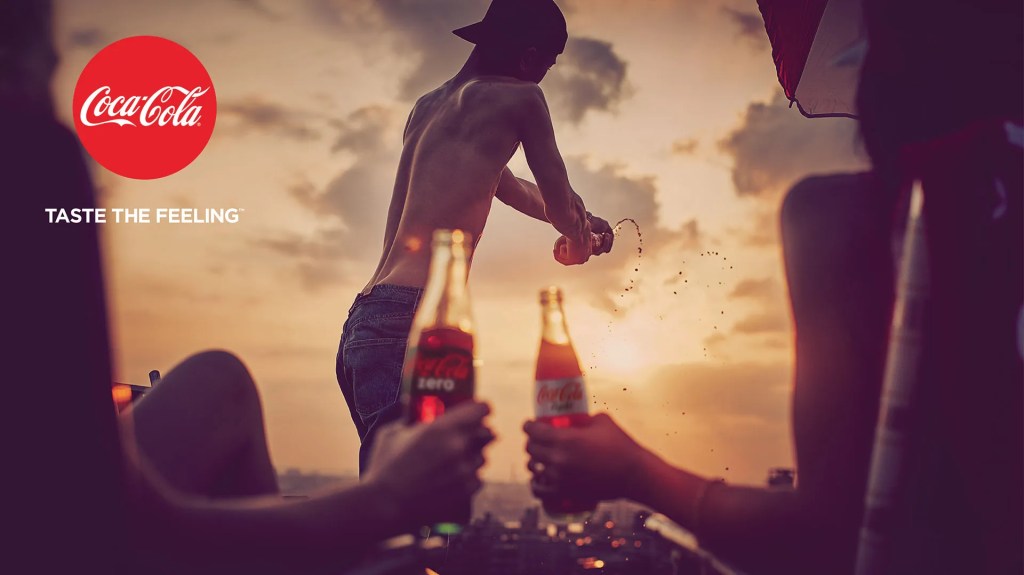

Prepare for a shock! You’re about to see a series of striking images (and one or two short videos) taken from advertising campaigns, protest movements, awareness drives, and art installations, all of which rely on shock factor and provocation to grab attention and highlight urgent issues. Examine the images, look closely at the details and ask yourself what issue the creator is concerned about. Try to decode the strategy behind it: what are the specific shock factor tactics (e.g. nudity, graphic imagery, hyperbole, and so on) being employed?

Once you’ve studied the images, make a judgment: Is the image effective? Does it feel like a bold, powerful move that could spark conversation and inspire action? Or does it cross the line into being gratuitous, tacky, or sensational, risking the message being lost in the outrage? In other words, decide whether the image is a ‘masterstroke’ or a ‘misstep’. Use the PPT and tracking grid resources below to conduct this activity:

2. Humour

“Whether they know it or not, costumed activists are contributing to a rich history of using humour… to mobilise against and challenge power.”

Blake Lawrence, writing for The Conversation

Embedded above is a short video from Dumb Ways to Die, which launched in 2012. The campaign was iconic because it used silly humour and absurdity rather than fear-based messaging. People can resist serious safety messages because they feel lectured to, or are desensitised to graphic images. Humour (even dark humour as seen here) lowers people’s defences, making viewers more receptive to messages that are still serious but delivered in a light-hearted way. Dumb Ways to Die features a catchy animated video with cute cartoon characters dying in ridiculous, exaggerated ways (like eating expired medicine or poking a bear) before ending with the reminder that being careless around trains is ‘the dumbest way to die.’

The approach was novel because it broke the mould of traditional safety ads that rely on serious imagery or stern warnings. Instead, it used (dark) humour and absurdity to make the message memorable and shareable, connecting with Australians who are famous for their dry sense of humour. In the age of social media, humour travels well and the campaign went viral globally because people wanted to share something funny with their friends, even though it carried a serious message. The success of this strategy led to multiple awards and the campaign even spawned a mobile game! (An honourable mention in the humour category should also go to St John’s Ambulance who made animated short The Chokeables, which you can see here.)

Activity: Research a Satirical Cartoonist

The Dumb Ways to Die campaign and the work of satirical editorial cartoonists share a common strategy: they use humour to deliver serious messages. Instead of relying on fear or graphic imagery, both approaches wrap uncomfortable truths in irony and exaggeration, making them more palatable for audiences. In Dumb Ways to Die, absurd scenarios are presented with cheerful animation and a catchy tune, creating a stark contrast with the grim reality of train accidents. This contrast mirrors the techniques of cartoonists like Patrick Chappatte, who often exaggerates political or social issues through caricature and surreal juxtapositions. Both forms of media provoke thought without resorting to gore, relying instead on wit and symbolic representation to spark dialogue. And both demonstrate how exaggeration and absurdity can disarm viewers’ resistance and so turn serious commentary into something people want to discuss and share around, amplifying the message.

For this activity, explore the world of satirical, editorial, and political cartooning. Browse the resource bank at Cartooning for Peace, where you’ll find cartoonists from different countries and cultural backgrounds. Alternatively, you may choose a cartoonist from the list below. As you browse, pay attention to recurring themes and stylistic choices that define the cartoonist’s work. Once you’ve selected a cartoonist, choose one or two images that best represent their style and message. Your task is to present these examples and explain what issue the cartoonist is addressing and how humour is used to deliver the message. Consider whether the humour relies on irony, exaggeration, absurdity, or cultural references, and reflect on why this approach is effective… or why you think it’s controversial.

3. Anti-Advertising (Culture Jamming)

“There are certain factions that will always try to ensure that audiences don’t think for themselves.”

Lucy Lippard, writing for Art in America

By now, you’ve explored how shock tactics, humour, fear, and other taboo-breaking strategies are used to grab attention, disrupt comfortable beliefs, and force viewers to rethink their assumptions. Anti-ads take this idea even further. Instead of reinforcing consumer myths or idealised lifestyles, anti-ads deliberately subvert them, exposing manipulation and lies and dismantling taboos. Like myth-busting campaigns, anti-ads thrive on provocation: they turn the familiar language and imagery of advertising upside down to reveal uncomfortable truths. Anti-ads share the same DNA as shock campaigns: they rely on disruption, irony, and confrontation to make people stop, think, and question what they’ve been told and sold.

A loud and provocative voice in the world of subversion is Adbusters. This Canadian-based non-profit organization and activist network is best known for its work in culture jamming and anti-consumerist campaigns. Culture jamming is the art of interrupting mainstream cultural messages, often through parody and visual remixing. For example, a car ad might be reworked to highlight the environmental damage it causes, or a fast-food logo might be reworked to expose obesity linked to junk food consumption. Founded in 1989, Adbusters publishes a magazine and creates provocative media that challenges mainstream advertising, corporate power, and consumer culture. Find a few examples of Adbusters work in the resource below:

Activity: Create a culture jamming image

Choose a mainstream advertisement, such as one for a fashion brand, a fast-food chain, or a tech product. Study the ad carefully: what is its core message? What myths or ideals is it selling: beauty, success, happiness, status?

Flip the message by sketching an Adbusters-style parody. Use irony, humour, or shock to expose the hidden assumptions behind the ad. Practice culture jamming by turning the language of advertising against itself to subvert the original intent and make viewers question what they take for granted. If you have the means (such as image editing software) bring your vision to life and share it with your classmates.

Learner Portfolio: Unmasking Cultural Myths

We live in a world surrounded by cultural myths; pervasive stories that shape how we think and even how we dream. These myths often promise happiness, success, or status. And they’re reinforced by movies, advertising, and social media. But how true are they? In completing this Learner Portfolio task, you’ll peel back the superficial surface of the myths around us to uncover the oft-unspoken reality that lurks beneath.

In pairs or small groups, choose a cultural myth from the briefs at the resource link below. You’ll find plenty of common cultural myths (like ‘Marriage guarantees a happily ever after’ or ‘Shopping bring happiness’). Investigate where your chosen myth comes from and how media keeps it alive through advertising, film and TV, social media, or elsewhere. Next, research the reality: what do the facts say? Look for data, expert opinions, and real-life consequences. Finally, see if you can find campaigns or movements that challenge the myth and present the truth in creative ways.

Once you’ve completed your research, present your findings in a presentation that busts the myth. Use visuals, evidence, and your spoken presentation skills to explain why questioning these myths matters.

Body of Work: Oliviero Toscani’s United Colours of Benetton Adverts

In April 2000, United Colors of Benetton fired its director of photography Oliviero Toscani over his advertising campaign entitled ‘Looking Death in the Face’ in which he featured the portrait photographs of inmates on death row as adverts for a retail clothing brand. For 18 years Toscani had been pushing the limits of advertising. From AIDS victims, to the bloodstains of a dead soldier, homosexual relationships, mixed race relationships, LGBTQ+ representation – Toscani shied away from nothing and produced some of the most controversial adverts in history. With each campaign came a new round of backlash, censorship – and press attention. After all, there’s no such thing as bad publicity! But this final campaign, released in January 2000 depicting death row inmates staring blankly into the camera behind the slogan, SENTENCED TO DEATH, proved to be Toscani’s undoing. Murder victims’ families spoke out, retailers and consumers dropped the brand, and sales consequently plummeted. An accusation that had been levelled at Toscani before – ‘what has this got to do with clothing?’ – was suddenly too loud to ignore. At the time, Rory Carroll of The Observer speculated that Toscani “almost certainly will never again reach a worldwide audience on the scale of his Benetton billboards” but it seemed that he had spoken a little prematurely. In 2017, Toscani rejoined Benetton once again.

In this Body of Work, you can explore some of Oliviero Toscani’s most provocative ad campaigns for United Colors of Benetton and investigate how these texts break social and cultural taboos.

Towards Assessment: Individual Oral

Supported by an extract from one non-literary text and one from a literary work, students will offer a prepared response of 10 minutes, followed by 5 minutes of questions by the teacher, to the following prompt: Examine the ways in which the global issue of your choice is presented through the content and form of two of the texts that you have studied (40 marks).

One or two of these images would be a perfect text to use in this assessed activity. Here are suggestions as to how you might use this Body of Work to create a Global Issue. You can use one of these ideas, or develop your own. You should always be mindful of your own ideas and class discussions and follow the direction of your own thoughts, discussions and programme of study when devising your assessment tasks:

- Field of Inquiry: Art, Creativity and Imagination

- Global Issue: The Artist’s Right to Shock and Offend

- Rationale:

Artists inspire and shape how we think, and they answer questions that we’re too afraid to ask ourselves. Creative individuals challenge the status quo and stimulate social change. They give us a new perspective and better understand our world. Without art and creativity, not only would our societies be boring and bland, but they would cease to grow and change. However, does that give artists and creative individuals license do say what they like, write without limits and show images that break cultural taboos? Answering this question would make a very interesting Individual Oral talk. An example of an effective pairing for this topic might be Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw. You could pursue the idea that Higgins, a kind of avatar for Shaw’s beliefs about society and class, is an extremely creative individual who feels entitled to dismiss the concerns of others should they clash with his own sense of what’s okay to say.

- Field of Inquiry: Culture, Community and Identity

- Global Issue: The Consequences of Breaking Taboos

- Rationale:

Toscani’s work for Benetton has been extremely controversial, and his images have frequently provoked outrage. Does it seem as if some taboos cannot be broken, even by famous iconoclasts such as Toscani? You could discuss this in your Individual Oral talk alongside a work such as (e.g.) The Vegetarian by Han Kang. In this novel, Yeong-hye breaks social taboos by refusing to wear a bra, refusing to cook meat dishes for her husband, or eat the meat dishes offered to her by her husband’s boss, and by asserting her right to live as she pleases, against the wishes of her own father. A focus on Yeong-hye’s brother in law, who breaks all kinds of acceptable boundaries in pursuit of his artistic vision, might also bear rich fruit.

Here is a recording of the first ten minutes of an individual oral for you to listen to. You can discuss the strengths and weaknesses of this talk as a way of improving your own oral presentations. Be mindful of academic honesty when constructing your own oral talk. To avoid plagiarism you can: talk about a different global issue; pair the Toscani images with a different literary work; select different passages to bring into your talk; develop an original thesis.

Towards Assessment: Higher Level Essay

Students submit an essay on one non-literary text or a collection of non-literary texts by one same author, or a literary text or work studied during the course. The essay must be 1,200-1,500 words in length (20 marks).

If you are an HL student, you might consider using Toscani’s Body of Work to write your HL Essay. Here are one or two examples of lines of inquiry suitable for this text – but remember to follow your own interests and the direction of your own class discussion to generate your own line of inquiry. It is not appropriate for students to submit responses to an essay question that has been assigned:

- How does Oliviero Toscani effectively use shock tactics to challenge cultural taboos in his photography work for the United Colours of Benetton?

Paper 1 Text Type Focus: charity appeals

At the end of your course you will be asked to analyze unseen texts (1 at Standard Level and 2 at Higher Level) in an examination. You will be given a guiding question that will focus your attention on formal or stylistic elements of the text(s), and help you decode the text(s)’ purpose(s). Below are examples of charity appeals. Use the examples of different texts to familiarise yourself with the genre tropes of this kind of writing; add them to your Learner Portfolio; you will want to revise text types thoroughly before your Paper 1 exam. You can find more information – including text type features and sample Paper 1 analysis – by visiting 20/20. Read through one or two of the sample responses then choose a new paper and have a go at writing your own Paper 1 analysis response:

key features of charity appeals

- Persuasive: the purpose of charity adverts is to make the reader take action, probably in the form of money or time. Adjacent to this is the need to raise awareness of social problems. Therefore, look out for all kinds of persuasive rhetorical features in charity appeals.

- Pathos: charity ads are likely to be more emotive than regular adverts. By appealing to emotions such as anger, pity, guilt, sympathy, and so on, charity adverts make it more likely that you will want to respond.

- Hard-hitting: like conventional advertising, charity appeals rely on visual elements to impact the viewer. An effective approach is to use hard-hitting shock tactics to spur the reader of this text type into action.

- Credibility: charity appeals need to be even more trustworthy than regular persuasive texts. Look for information that suggests your donations will make a positive change, perhaps in the form of facts and statistics.

- Metonymy: social problems like hunger and poverty are too large for one person to help solve; so charity ads often introduce you to a single individual who represents all those who your donation goes towards helping.

- Direct address: charity ads will often address the reader with the word ‘you’, striving to make a strong connection. If a person in the advert is making eye contact with you, this is a kind of visual direct address.

Further Reading

- Ads Designed to Shock You (Business Insider. Caution: graphic images)

- New Anti-Smoking Campaign is a Shocker (Solopress blog)

- Shock Advertising or Animal Cruelty? (Advertising Insights blog)

- Public Support for Charity Shock Ads (civil society news report)

- Spencer Tunick Wants Volunteers (CNN report)

- Nast and Reconstruction (video exploring historical political cartoons)

- The Power and Danger of Political Cartoons (Rijkstube explainer)

- Portland’s Dancing Frogs Challenge Tyranny with Humour (UTS newsroom article)

- ‘La Pieta’ AIDS Campaign (online article)

- United by Half (Benetton’s upcoming Indian campaign)

- United Colours of Benetton Campaign Archives (Historical Adverts)

- We Criminalise Political Stunts At Our Peril (from The Guardian)

- Benetton’s Most Controversial Adverts (image gallery)

- ICE Protest Frogs Have a Long History (The Marshall Project article)

- The Most Shocking Ads Explained (youtube)

- The ad campaign that launched a thousand critiques (NPR report)

- ‘I Wish My Son Had Cancer’ (article at The Guardian)

- Exploring Occupy Wall Street’s Adbuster Origins (NPR report)

- Advertising Pollutes The Brain (Lampoon magazine article)

Categories:Taboo or Not Taboo