FREE CHOICE / translated work (JAPANESE) / C20TH / asia / japan

“These stories show us Japan as it’s experienced from the inside… [they] take place in parallel worlds not so much remote from ordinary life as hidden within its surfaces…”

The New York Times Book Review

Introduction

Haruki Murakami (in Japanese, 村上 春樹) was born in Kyoto in 1949 and moved to Tokyo to attend Waseda University. After college, Murakami opened a small jazz bar, which he and his wife ran for seven years. If you are ever in Tokyo you can still visit the Peter Cat today. Murakami’s love of music pervades his books. Many of his characters pass the time listening to music and even the title of a well-known novel is named after a Beatles song: Norwegian Wood.

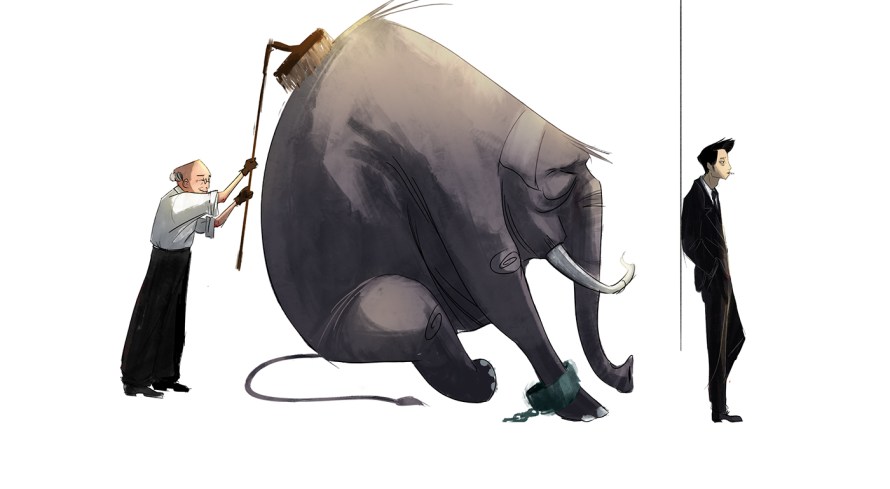

His first novel, Hear the Wind Sing, won the Gunzou Literature Prize for budding writers in 1979. He followed this success with two sequels, Pinball, 1973 and A Wild Sheep Chase, which all together form “The Trilogy of the Rat.” Since then Murakami has written over a dozen novels, works of non-fiction and short story collections, including The Elephant Vanishes (originally published in 1993). His work has been translated into more than fifty languages, and nominated more than once for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

It’s almost impossible to pin down a single theme in Murakami’s work. When asked about the purpose of his writing in a recent interview, he replied: “When I was in my teens, in the 1960s, that was the age of idealism. We believed the world would get better if we tried. People today don’t believe that, and I think that’s very sad. People say my books are weird, but beyond the weirdness, there should be a better world. It’s just that we have to experience the weirdness before we get to the better world. That’s the fundamental structure of my stories: you have to go through the darkness, through the underground, before you get to the light.”

- Stories from The Elephant Vanishes by Haruki Murakami

- A letter from the editor of The Elephant Vanishes

IB Student Learner Profile: balanced

“We critically appreciate our own cultures and personal histories, as well as the values and traditions of others. We seek and evaluate a range of points of view, and we are willing to grow from the experience.”

In these stories, an elephant disappears from a zoo through the locked door of a cage; a ravenous hunger overwhelms a young married couple, bringing out the wife’s hidden criminal tendencies; and a little green monster who can read minds burrows up through a woman’s backyard. It’s easy to get lost inside Murakami’s alternate worlds, and it can be hard to find your way back to reality. Some characters get stuck in a world bereft of stimulation; others try to escape by plunging into the past, fantasy worlds, or even alternate realities. People feel bewildered by the world and seek answers to the point of their own existences. Above all they struggle – often unsuccessfully – to find balance in their lives.

IB Lang and Lit Concept: perspective

A criticism that is sometimes levelled against Murakami’s writing is that his narrators, from book to book, are overly similar. Most are young men of a certain age (mid-twenties to mid-thirties) who have dropped out of mainstream society and seem to be searching for answers to questions of life and purpose that they haven’t yet properly formulated. His female characters tend to be ambiguous, often taking supporting roles and having hidden thoughts and motivations – yet they leave a huge impact on the hero’s life and are often a reason for the strange journey he undertakes. As you read the stories in this collection, ask whether these criticisms are wholly fair and explore the effect reading through the eyes of men (or occasionally women) has on your perspective on The Elephant Vanishes.

1. The Wind-up World

“I’m in the kitchen cooking spaghetti when the woman calls…”

The Wind-up Bird and Tuesday’s Women

A man stands in his kitchen cooking spaghetti when the phone rings, not once, not twice, but three times. He’s irritated and doesn’t want to talk to whomever is on the other end of the line. It soon becomes clear that this is a man of routine; even ironing his shirts needs planning out into twelve meticulous steps. Yet, despite his best efforts, our narrator is drawn out of his private world as he finds himself sent on a quest to find a disappearing cat.

Haruki Murakami establishes the tone and motifs of his anthology in the first story of the collection. As in many of Murakami’s works, we find ourselves in a world in which the narrator seems stuck in a rut and rarely ventures out of his house. But he nevertheless has encounters with new and eccentric people. In this section, you’ll discover how readers can understand the nature of the narrators’ daily existences in Murakami’s short stories.

Resources

Wider Reading

Murakami’s Motifs

In 1998, Murakami published his novel The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, continuing the story of The Wind-up Bird and Tuesday’s Women. We discover the narrator’s name is Toru Okada, and the missing cat is only the beginning of his troubles. When his wife also disappears, he ventures into a mysterious netherworld underneath Tokyo, encountering a bizarre group of allies and antagonists, including an old Japanese soldier, a mute boy who can read minds, and a clairvoyant woman who visits him in his dreams.

Learner Portfolio: The ‘Wind-up World’

Murakami’s stories take place in a version of Japan that seems real… but feels odd in many ways. Houses are empty and abandoned, passageways have no entrances and exits, shadows cling motionlessly to the ground. People pop up out of the blue, and disappear again with no warning. Above everything sits the wind-up bird in his tree, as if all the world is a clockwork toy.

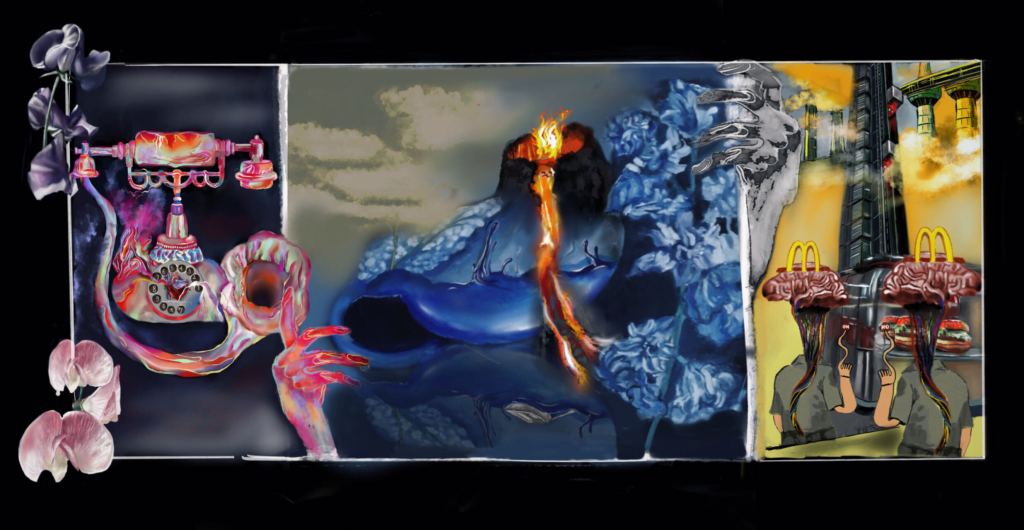

Create a visual representation of the ‘wind-up world’ of Murakami’s short stories. This could be a mind-map, spider-diagram, poster, collage, or even a piece of artwork, like the brilliant triptych you can see above. Share your work with your classmates, make a classroom display, and add a reflection to your Learner Portfolio.

2. Hidden Motivations

“Why my wife owned a shotgun I had no idea… Married life is weird, I felt.”

The Second Bakery Attack

A married couple lie in bed, suffering from the most profound hunger. The fridge is empty – except for some onions and a bottle of beer. To distract him from his hunger pangs, the man tells his wife a story of how, many years ago, he once robbed a bakery. Unexpectedly, the story seems to wake something up inside of her, and she persuades him to orchestrate a ‘second bakery attack.’

As with the first story in the collection, Murakami presents women characters who seem to have strength and emotional depth that is conspicuously lacking in the male narrators. But the female characters are also shrouded in mystery and ambiguity. In this section we’ll take a closer look at the female characters in Murakami’s stories.

Murakami’s Motifs

In this story, the central couple hold up a Mcdonalds as they can’t find a traditional bakery to rob. This isn’t the only time Murakami features a popular fast food chain in his writing. In his novel Kafka on the Shore, a tricky spirit takes the form of Colonel Sanders – popularly known as the KFC logo – and a top hatted Johnny Walker. who famously strides across many a whiskey bottle, makes a surprise appearance as an evil cat killer.

Resources

Wider Reading

Learner Portfolio: Men and Women as Foils

‘Haruki Murakami’s stories almost always involve grown men who have not fully developed emotionally and several strong-willed women who force them to question their world-views.’

The narrator of The Second Bakery Attack’s wife is one of the more enigmatic and yet dynamic characters in Murakami’s stories. She is decisive in her actions throughout but unclear, often, in her motivations. In this she shares much with Murakami’s other female characters. In this portfolio entry, complete a piece of work that compares the male and female characters from The Elephant Vanishes story collection. You could create a mirror profile, complete a Venn diagram, or write a compare and contrast essay. It’s up to you whether you focus on particular characters, or try to summarise the essential differences between men and women across multiple stories.

3. Breaking with the Past

“…what was going to redeem this imperfect life of ours, so fraught with exhaustion?”

Sleep

A woman finds it impossible to sleep. This isn’t the first time she’s suffered from insomnia, but it is the strangest. To begin with, she’s not tired. In fact, she’s able to access previously unknown reserves of energy and creativity. But as time passes, things become increasingly weird as she is driven to ever-more desperate measures to figure out what’s going on.

Throughout The Elephant Vanishes, Murakami elegantly draws a portrait of the post-imperial country of Japan; in his eyes it is a dull place of electrical appliance stores, fading institutions and rapidly diminishing men. Nowhere is this faded land more evocative than in Sleep, one of the stories central to the collection.

Resources

Murakami’s Motifs

By this point in the anthology, the reader has accepted that characters can communicate and engage in substantive activity in dreams. This is sometimes an oddity to the various characters – but some of them also seem to accept that dreams can have significance. Murakami writes in a particular genre of ‘magical realism’, where unexplained events, disappearances, dreamers, soothsayers, coincidences, freak weather events and other similar phenomenon exist in the world.

Learner Portfolio: Practise for Paper 1 (Literature students only)

If you are a Language A: Literature student, at the end of your course you will sit Paper 1: Guided Literary Analysis. This paper contains two previously unseen literary passages. SL students write a guided analysis of one of these passages; HL students write about both passages. The passages could be taken from any of four literary forms: prose, poetry, drama or literary non-fiction. Each of the passages will be from a different literary form.

Here is a small selection of passages taken from the anthology; as The Elephant Vanishes is a short story collection, the literary form is ‘prose’. Each passage is accompanied by a guiding question to provide a focus or ‘way in’ to your response. Choose one passage and complete this Learner Portfolio entry in the style of Paper 1: Guided Literary Analysis.

4. Invisible Forces of Evil

“I’d like to believe I’ve got my own morals. And that’s an extremely important force in human existence. A person can’t exist without morals.”

Barn Burning

In Barn Burning, one of the most compelling stories in the collection, our male narrator begins an ambiguous relationship with a part-time model and amateur mime artist. Their relationship seems odd, but neither of them seem to mind. But, after she goes on a sudden trip to North Africa, things begin to change between them. While there, she met a new man and one Sunday, out of the blue, she calls up the narrator and asks if she can introduce them. Since his wife is out of town and he’s at a loose end, the narrator agrees. Later, in confidence, the stranger confides in the narrator that he enjoys a very unusual hobby indeed: once every few months he chooses a barn and burns it down.

Resources

Wider Reading

- Hikokomori (article from the BBC)

- Isolated Lives of Japan’s Social Recluses (National Geographic photo-essay)

- Haruki Murakami (BBC 3 radio profile)

- What You Can Learn From Japan’s Lost Decade (thebalance article)

- Lost Decade in Japan (youtube video explainer)

- Japan: the Fading Economy (Economics Explained video)

Murakami’s Motifs

After he left college, Murakami owned a small jazz bar called the Blue Parrot in Tokyo. His love of music is apparent in every book he writes. In Barn Burning, two characters discuss a very strange hobby whilst listening to an eclectic range of music, from Miles Davis, to Strauss, to Ravi Shankar. Most of Murakami’s stories contain references to classical musicians, songs, pop albums and more. Visit this brilliant compendium of all the references to music in The Elephant Vanishes stories – and beyond.

Learner Portfolio: Japan’s Lost Decade

Throughout The Elephant Vanishes story collection, the reader is haunted by an elusive feeling that things in the world are not quite right. There’re subtle, insidious forces at work that drain the world of vitality, leaving characters adrift in a landscape that feels increasingly disjointed and emotionally hollow. Murakami’s protagonists find themselves stuck in a kind of existential limbo, going through the motions of life without feeling like they’re truly alive. People are surrounded by modern conveniences, technology, and material goods, but they feel spiritually and emotionally starved. Murakami’s evil forces are not villains in the traditional sense, but invisible forces that leech colour, vitality, and purpose in ways that are hard to name… but nevertheless deeply felt.

Using the Wider Reading resources above, and any other sources you might find, conduct some research into the context and background of Murakami’s work. Then, try to link what you discover to the ideas you’ve learned and discussed in these stories. You could create a chart, a mind-map, or simply take notes in a concise format (such as using the Cornell notetaking method). Share your findings, and add your notes to your Learner Portfolio.

5. Alienation and Empathy

“My husband left for work as usual, and I couldn’t think of anything to do.”

The Little Green Monster

A lonely housewife looks out at an oak tree that stands in the center of her garden. Her husband is at work and she seemingly has nothing to do. Suddenly, a horrifying little creature burrows its way out from underneath the tree and forces its way into her house. Initially, the woman is frightened – but the monster has the power to read minds, and she begins to communicate with it. Then, things take an unexpected turn, and the reader is left wondering who is the real monster in this story?

Resources

Wider Reading

Murakami’s Motifs

The little green monster is a typical Murakami creation. In his 2019 novel Killing Commendatore, an artist is disturbed one night when he hears a noise in the attic. On investigation he finds a previously undiscovered painting hidden away – and things only start to get weirder when one of the little characters in the painting jumps out and starts to talk!

Learner Portfolio: Practise for Paper 2

Write this Learner Portfolio in the style of a practice Paper 2 response. You can use one of the prompts below, or another prompt given to you by your teacher. Although Paper 2 requires you to write about two literary works, for the sake of this exercise you could focus only on your response to The Elephant Vanishes, or you could try to compare your ideas to another literary work you have studied (visit this post for more help with Paper 2):

- Judging by literary works you have studied, what would you say are the main causes of unhappiness and how are these presented?

- Explore how women are represented as stronger than men in the literary works you have studied.

- Animals and images drawn from the world of animals are a rich source of inspiration for writers. Discuss how animals are used to develop central ideas in works of literature you have studied.

- Writers can present their ideas in unusual or thought-provoking ways. How, and to what effect, has this been shown in two works you have studied?

6. The Elephant Vanishes… (and other animals)

“People are looking for a kind of unity in this kit-chin we know as the world. Unity of design. Unity of colour. Unity of function.”

The Elephant Vanishes

The Elephant Vanishes is the title piece of the short story collection, but Murakami has saved this story till last. An old elephant and its keeper suddenly disappear one night from a dilapidated old zoo. As a chronicler of the elephant’s disappearance, the narrator of this story recounts news coverage of the incident, remembers the futile attempts of the townspeople to find the elephant, and obsesses over the strange facts surrounding the case. As the story progresses, the narrator continues to feel confused by the elephant incident and saddened by the disappearance of the elephant and its keeper. He feels ‘the air of doom and desolation’ hanging over the empty elephant house, and he continues to visit the zoo forlornly, seemingly searching for something that has vanished along with the elephant.

Resources

Wider Reading

Murakami’s Motifs

In Murakami’s fiction, it’s not only animals who disappear, but people too. Mirroring how some slip through the cracks of society, the disappearance of animals and people often represent the loss of something deeper and existential. Whether it’s the elephant vanishing here, cats getting lost in The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, or Sumire disappearing in Murakami’s 1999 novel Sputnik Sweetheart, vanishing people and animals allude to themes of loss, the fragility of relationships, and the porous boundary between our conscious and unconscious worlds.

Learner Portfolio: Murakami Mixtape

Murakami is an author with a distinctive style. Once you’ve read one or two Murakami stories, you can recognise his signature flourishes in other stories and novels you read. To take but one idea, the disappearing cat – studied here in the story The Wind-up Bird and Tuesday’s Women – repeats itself in his masterpiece novel The Wind-up Bird Chronicle and in his bestselling Kafka on the Shore. Another ‘Murakami Motif’ is his juxtaposition of men and women: with notable exceptions (Sleep, for instance, or his novel IQ84) his narrators tend to be male, around thirty years of age, and undergoing some kind of crisis that compels them to drop out of the rat race. By contrast, his female characters are young, vivid, lively, often guiding the men in finding the answers they seek.

Imagine you are writing a new Murakami story. What recurring elements, motifs, and signature flourishes might it contain? What plot points might you include? Where are the likeliest settings going to be? What kinds of characters can you transport from one story to another? Create a ‘Murakami Mixtape’ of all the elements that you think makes a story distinctively – and unmistakably – Murakami.

(For those who are creatively minded or enjoy a creative writing challenge, you might even follow up this activity by writing a pastiche, a story that pays homage in style and flavour to that of a famous writer. Here’s a story called The First Friday, written by a student, that admirably captures the atmosphere, and other characteristics, of Murakami’s writing. Going even further, here’s a film made by students who took inspiration from Murakami into their Film class!)

Towards Assessment: Individual Oral

Supported by an extract from one non-literary text and one from a literary work (or two literary works if you are following the Literature-only course) students will offer a prepared response of 10 minutes, followed by 5 minutes of questions by the teacher, to the following prompt: Examine the ways in which the global issue of your choice is presented through the content and form of two of the texts that you have studied (40 marks).

The Elephant Vanishes would be a good choice to discuss in this oral assessment. The stories explore themes of people in society, connectedness, consumerism, communication, the roles of men and women in society, nature, and more. Now you have finished reading and studying Murakami’s short stories, spend a lesson working with the IB Fields of Inquiry: mind-map the stories, come up with ideas for Global Issues, make connections with other Literary Works or Body of Works that you have studied on your course and see if you can make a proposal you might use to write your Individual Oral. Here are one or two suggestions to get you started, but consider your own programme of study before you make any firm decisions about your personal Global Issue. Whatever you choose, remember a Global Issue must have local relevance, wide impact and be trans-national:

Literary pairing

Body of work Pairing

- Field of Inquiry: Culture, Community and Identity

- Global Issue: the consequences of consumer-capitalism on communities and individuals

- Rationale:

In these stories, Murakami portrays a consumer‑capitalist world through which characters drift, experiencing isolation, emptiness, and disconnection from one another. The motif of vanishing points to something missing from a hyper-commercialised world. A work originally written in English that manifests the same issue is Glengarry Glen Ross by David Mamet. In the microcosm of the sales office, men are pushed by capitalist, profit-driven incentives to lie, cheat, and steal, undermining their connection with each other – and with their own humanity. An alternative work originally written in English that you might choose instead is Top Girls by Caryl Churchill, which shows how capitalism warps Feminism in the context of a women-run talent agency.

- Field of Inquiry: Science, Technology and the Environment

- Global Issue: how urbanisation and globalisation erode our connection to nature

- Rationale:

In Murakami’s stories, as cities expand and consumer culture accelerates, the living world slips further and further out of sight. Characters live inside their own little compartments, but feel unmoored and disconnected from life and living. A body of work that might help explain this issue is George Monbiot’s essays and articles. He argues that our world is no longer shaped by forces of nature, but by global economic and corporate forces who see nature as something to be commodified, extracted and consumed. An alternative choice could be Alison Wright’s Human Tribe portraiture and photography, which reveals marginal, indigenous, and minority cultures that are still fully immersed in nature. She offers an antidote to the ecological decline Murakami implies.

Towards Assessment: Higher Level Essay

Students submit an essay on one non-literary text or a collection of non-literary texts by one same author, or a literary text or work studied during the course. The essay must be 1,200-1,500 words in length. (20 Marks).

Once you’ve finished studying Murakami’s collection of short stories, and your mind is turning to the Higher Level Essay you have to write, The Elephant Vanishes would make a fertile ground for topics. Here are one or two examples of lines of inquiry suitable for this text – but remember to follow your own interests and the direction of your own class discussion to generate your own line of inquiry. It is not appropriate for students to submit responses to an essay question that has been assigned:

- How does Haruki Murakami use motifs of vanishing and forgetting throughout The Elephant Vanishes stories to explore Japanese society’s problematic relationship with the past?

- How does Haruki Murakami shape liminal spaces in ways that suggest the impossibility of personal reinvention in The Elephant Vanishes collection of short stories?

Categories:Prose

This is amazing! I am using some of your ideas for After the Quake. About to dive into Murakami for the first time so this is great. Thank you for sharing your resources!

LikeLike

Hi, glad you like it. Actually I have yet to read After the Quake – but i mean to fix that soon. Hope your classes go well :o)

LikeLike