Unseen Text: Hey! I Was Reading That

Text Type: Comic Strip

Guiding Question: How and with what effect do written text and images make meaning for the reader?

It can be tempting when you sit down to write your Paper 1 analysis to rush to show off your knowledge of different text types, especially after you’ve made all that effort to learn and revise niche genres such as comics and cartoons. Finally, you get to explain fancy techniques like emanata, colour symbolism, or graphic weight! However, the guiding question accompanying this past paper asks how meaning is created – and the central meaning of a comic rarely depends on features such as emanata or colour schemes. This response shows how the figures in the images combined with the words of the text create the meaning of the strip. Only once this is established does the answer analyze supporting compositional features. Of course, this is only one way of approaching this text. Alternative responses can be equally valid:

Sample Response:

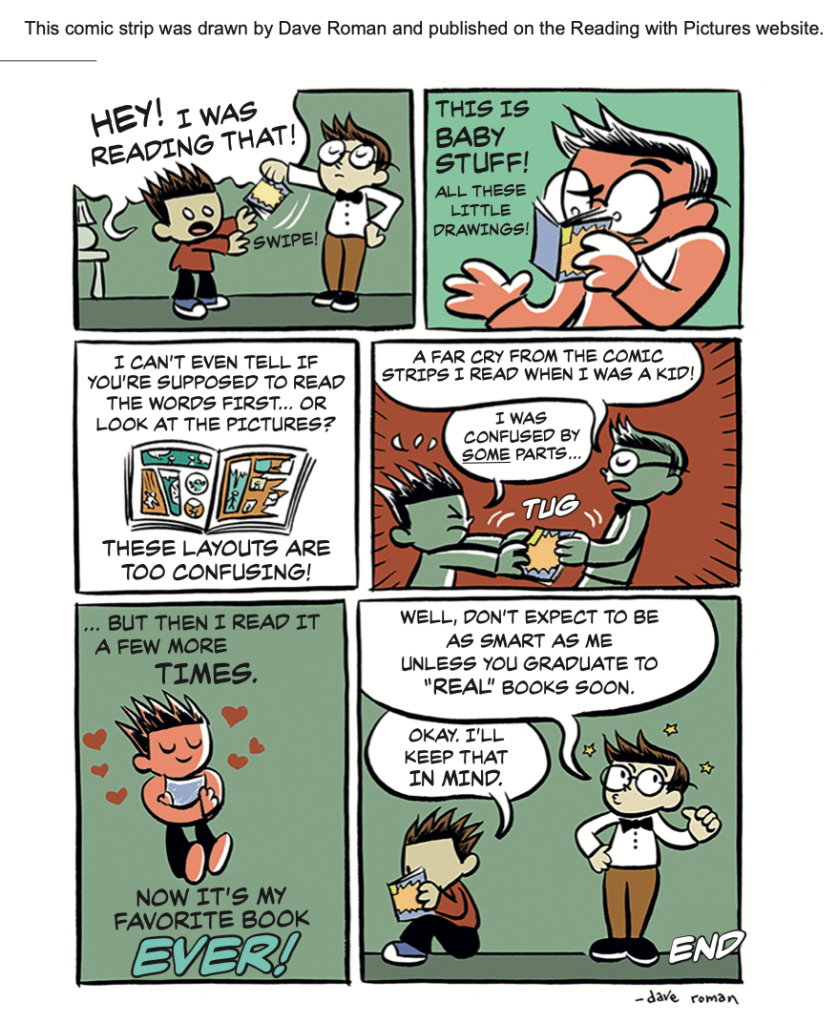

Dave Roman’s comic strip explores attitudes towards reading, in particular the idea that reading graphic novels or comic books is inferior to reading ‘real’ books. Through conflict between two boys, Roman symbolises a stuffy, elitist point of view that dismisses comic books as childish, and a more open-minded idea about the joy of reading comic books at any age. As a comic artist himself, presumably Roman’s perspective aligns with the younger character, who comes across as the more sympathetic of the two.

Firstly, Roman personifies conflicting attitudes towards comics in the contrasting figures of two children, possibly siblings, who are arguing over a comic book. The younger sibling is drawn with spiky hair and round, open eyes which signifies his youth and makes him seem like the more relaxed and approachable of the two characters. He personifies casual readers of his age who enjoy reading comic books. The final panel represents this through his body language; he is pictured sitting on the floor with his head buried in the pages of his comic book, enjoying the immersive and imaginative experience of reading. By contrast, the older boy is drawn to represent a stuffy, elitist reader. He wears a buttoned-up shirt and a bow tie which represents his snide, elitist attitude. He wears glasses, a signifier of his supposed intelligence, through which his eyes are often slanted downwards condescendingly, representing how he looks down on the younger boy due to his preference for reading comics. When pictured in the same panel, the boys are always positioned on opposite sides, visually suggesting how they take up opposing positions over the topic of reading comic books. Therefore, the artist uses the contrasting figures of the two boys, plus their positioning in the frames, to represent contrasting viewpoints on reading comic books: one enthusiastic and non-judgmental; one elitist and condescending.

However, while the older boy looks down on the younger for his reading taste, Roman uses ironic dialogue to reveal the shortcomings of his dismissive attitude towards comic books. The older boy is captioned saying: “This is baby stuff! All these little drawings!” His choice of words and exclamatory tone conveys his opinion that comics are infantile, suitable only for ‘little babies’ to read. The word ‘stuff’ is dismissive of comic books as lacking substance compared to “real books.” Contrastingly, he adopts an adult register, using words such as “far cry” and “graduate,” conveying his self-perception that he has outgrown comics. Yet Roman uses irony to draw attention to how his dismissive attitude conceals his own shortcomings. Despite his pretentions, the older boy “can’t even tell if you’re supposed to read the pictures first,” which is ironic given he dismissed the comic as childish. In reply, the younger boy’s dialogue ironically reveals a more mature soul. He admits to being “confused by some parts,” but, through persistence, he came to enjoy reading and says, “now it’s my favourite book”. His statements suggest how an open-minded approach to reading can lead to a rewarding experience. Therefore, Roman uses the boys’ ironic dialogue not only to present their conflict of opinion, but to further imply how those with arrogant and superior attitudes can be quick to dismiss activities that they themselves don’t understand but that others may value.

Finally, Roman places a small cartoon comic book in every panel not only to show what the boys are arguing over, but to illustrate his overall meaning that comics have inherent complexity and worth. He dedicates the third panel to a close up of the comic book’s inside so we can see panels of different shapes and sizes, revealing how this genre of reading has evolved its own complexity over time. This runs counter to the older boy’s argument that comic books are childish, and aligns with the writer’s view that comics, like any literary genre, have a spectrum of ‘difficulty levels’ that are suitable for readers of all ages. At the same time, though, the reader is drawn to accept the younger boy’s argument: while the layout may appear confusing at first, it doesn’t seem impossible to decode. As if to prove his own argument, the artist employs the codes and conventions of comic books in his own panels. For examples, the boys’ conflict over the comic book is illustrated with action lines and the word “tug” emanating from the book in between them. Even casual readers can interpret these emanata to mean a ‘tug-of-war’ over the book. Secondly, the hearts and stars in the fifth and sixth panels symbolise the boys’ contrasting attitudes: the younger boy loves his comic book hobby, despite the scorn he’s receiving, while the stars around the older boy’s head in the last panel indicate his high opinion of himself. Therefore, through placing a comic book at the center of his story, and using conventions of comic book art to embellish his panels, Roman constructs the meaning that comics have their own inherent complexity that goes beyond age groups. The prerequisite for enjoying comics is not age, but dedication and love for the form itself.

In conclusion, Dave Roman’s argument for reading comics is presented through the symbolic figures of two readers, one dismissive and snide who readers are likely to dislike, the other warm and encouraging who comes across as more sympathetic. Roman’s comic strip itself embodies the younger boy’s argument, as he shows that features such as irony, humour, and symbolism can make themselves as meaningful in a simple comic strip as they can in the most demanding of prose novels.

Categories:Paper 1 Analysis